Welcome to the Year of the Elections, Bloomberg’s newsletter on the votes that matter to markets, business, and policy amid the most fragmented geo-economic landscape in decades.

The far right is set to gain seats in this week’s European Parliament elections, but internal disputes among many nationalist groups will limit their influence and might offer mainstream parties some breathing space.

The Alternative for Germany (AfD) in particular has suffered a number of setbacks in the past few weeks.

A series of scandals shook the party, ranging from a conference on the planned deportation of asylum seekers and naturalized Germans to a bribery and spying affair, which tainted the party’s lead European Union candidate, Maximilian Krah, and his deputy, Petr Bystron, a member of parliament. The AfD leadership told both candidates to stop campaigning.

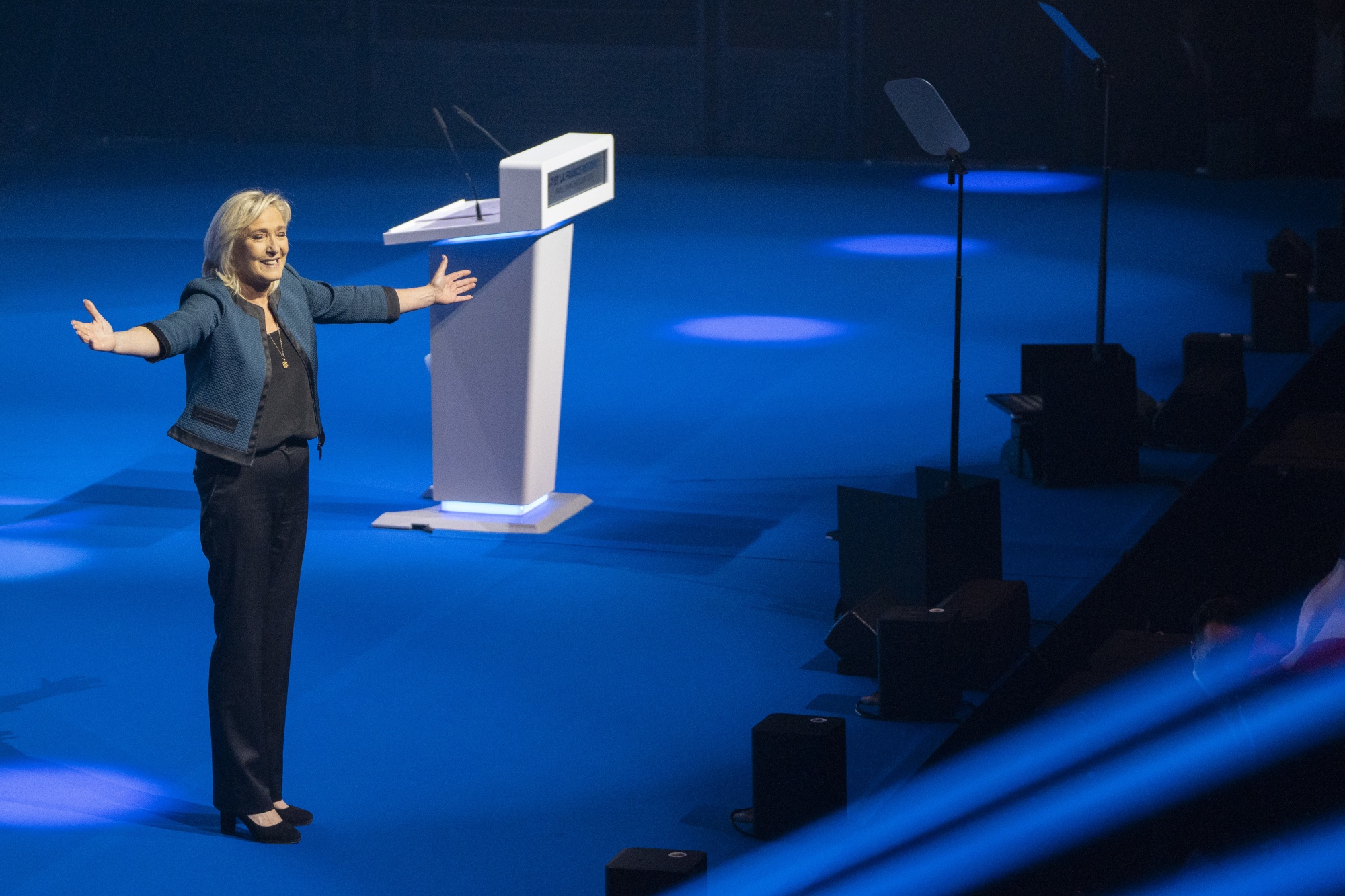

Even worse: Two weeks ago, French nationalist Marine Le Pen publicly distanced her National Rally (RN) from the AfD after Krah said in an interview with an Italian newspaper that not all members of the Nazi SS paramilitary organization were criminals. The Identity and Democracy alliance in the European Parliament, which includes RN, expelled the German party.

A Shift to the Right?

Meloni’s ECR and Le Pen’s ID look set to gain seats in the EU elections

Although this move was purely symbolic, since it didn’t affect any decision making in the current EU parliament, it showed how isolated the AfD has become in Europe.

Unlike Le Pen and Italy’s far-right leader Georgia Meloni, the AfD’s co-leader, Alice Weidel, has failed to move her party more into the political mainstream. Plus, it’s unclear whether the AfD will be able to join a political group again in the newly elected EU parliament.

As a result of this series of mishaps, the AfD has lost its momentum in the polls. In the most recent national EU poll from the Insa institute, it dropped from a peak of 23 percent in July 2023 to 16 percent on June 1. But it remains the second-most popular party in Germany, ahead of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s Social Democrats.

Without the AfD, ID is projected to win 68 seats in the assembly, according to a polling average compiled by Europe Elects. That would be down from the December projection when it appeared on track to win 93.

In spite of the surge projected by the polls, European officials remained skeptical that the results would lead to the rightist tide that some have predicted.

Their disruptive impact would depend on whether the two main voices of these parts of the spectrum, Le Pen and Meloni, could join forces in a single group in the EU chamber, said some diplomats, who doubted that the Italian prime minister would go for that option.

The increase of the support for hardline parties against some landmark EU policies, including green rules, has come amid the rising impact of hacking and disinformation against the candidates and the EU institutions.

Some campaign officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter, expected a significant increase of malware activity during the final couple of weeks.

European Commission President and EPP candidate Ursula von der Leyen’s website was one of the targets of such attacks.

European Economy Q&A

Craig Stirling, Bloomberg’s senior editor for economy and government in Europe, gave us his perspective.

The European Central Bank is set to cut interest rates and growth is rebounding. Does that mean the European economy is entering a sweet spot?

Euro-zone officials would dearly wish so, but that seems unlikely. The European Commission described its forecast last month as a “gradual recovery amid high geopolitical risks” — and the 0.8% expansion it predicts for the currency region this year is less than half of the average seen in the five years before the pandemic.

While the Brussels executive anticipates a stronger pickup next year, the dangers posed by Russia’s war in Ukraine raging nearby with the threat of another energy shock seem likely to overshadow the economy for years to come.

When you look over the next five years, what will be the key economic challenges for the next commission?

Among the longstanding problems officials will face are the region’s persisting lack of productivity growth, its waning competitiveness, and the continuing fragility of a single currency that isn’t matched by a fiscal union.

More recently, the need to retool the economy for climate change and a push to pool defense spending has been preoccupying Brussels, while the implications of an aging population is another issue rapidly rising on its list of priorities.

One complication could be the possibility of a less compliant European Parliament if the elections deliver a swing against mainstream parties toward populist groups more opposed to the bloc’s legislative agenda.

Euro-area finance ministers have agreed to a new set of debt and deficit rules that could, in theory at least, start to put pressure on governments next year. How do you see that playing out?

This could become a real test both of the new rules and of the commission’s potency. Five members of the bloc have borrowings exceeding 100% of output. Of those, Italy is predicted by Scope Ratings to replace Greece as the region’s most-indebted nation within three years, while both France and Belgium continue to run particularly egregious deficits.

Officials know from the bitter experience of the region’s sovereign debt crisis that a failure to repair public finances just stores up trouble for the future. But testy electorates, the need to rearm to deter and the challenge of meeting existing pension commitments funded by proportionately shrinking workforces will make that a tough job to achieve.